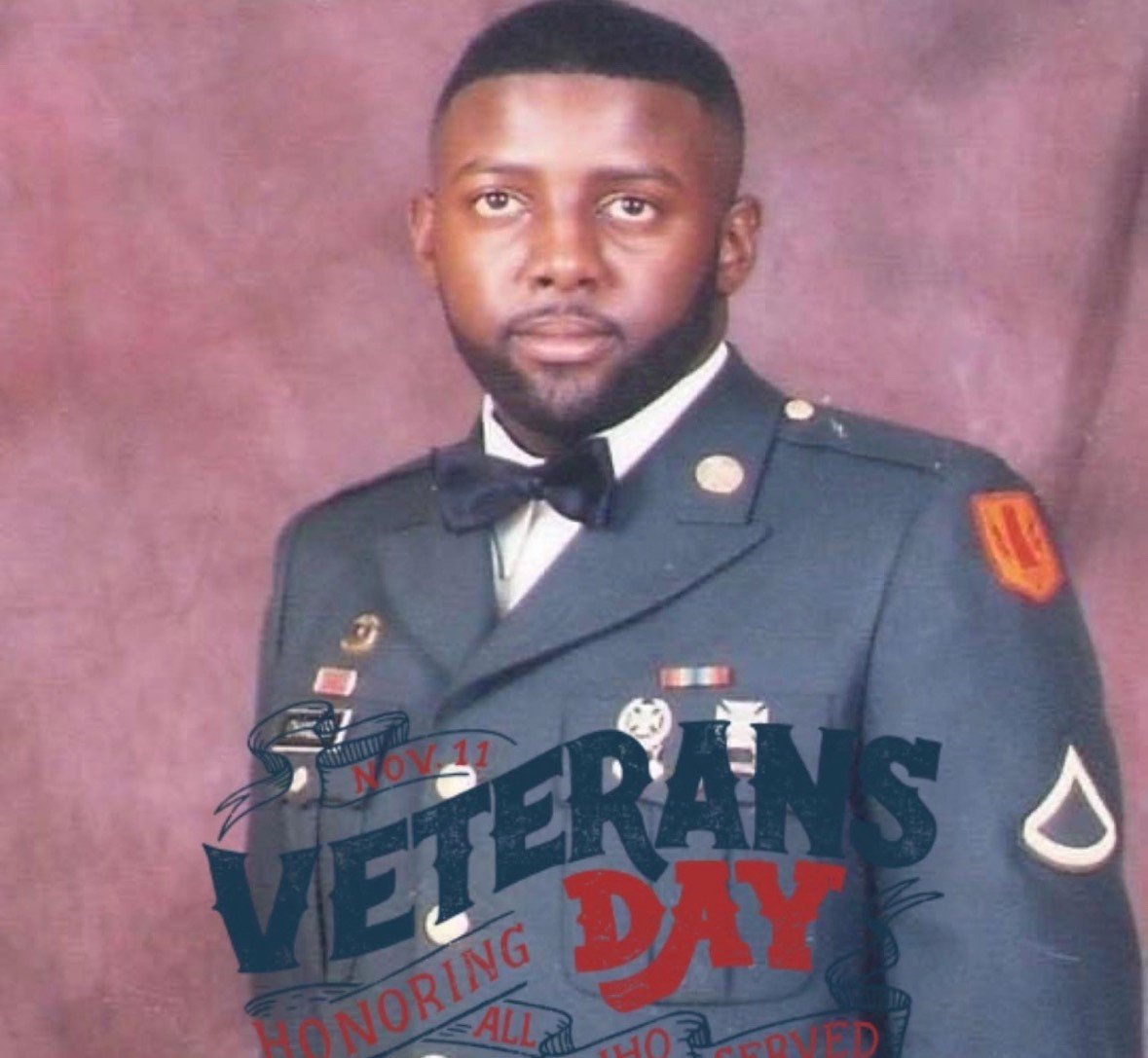

At 47, Tyrone Chandler carries himself with the quiet discipline of someone who’s seen too much but found a way forward anyway. He served 10 years in the Army before retiring early due to injury, but the real battles began when he came home.

“I enlisted right out of high school in ’95,” he says. “My grandfather, my dad, cousins, uncles, aunts — military family. They had influence on me through JROTC in high school. When I made the decision to enlist, everyone was excited.”

Basic training at Fort Jackson was hot summer misery, but Chandler was prepared. His high school JROTC program had taken them to “Camp Victory” during summers — a taste of what military training would be like.

“So, I knew what to expect. The drill sergeants yelling and screaming, the smoke sessions when you mess up. It was tough, but I was ready for it.”

Learning to jump out of planes

After basic training and Advanced Individual Training (AIT) in Virginia, where he became a 77 Fox specialist (now called 92F) — a petroleum supply specialist — Chandler got orders for additional training.

“They sent me to another school for hazmat certification, then to Fort Benning for Airborne School. That’s where I learned to jump out of planes.”

He describes the experience with the matter-of-fact tone of someone who’s done extraordinary things: “You do five jumps. First one’s a static line jump — you’re attached to the plane. You have your main parachute on your back, reserve on your front. They call out ‘Two minutes! Stand up! Hook up!’ and everybody lines up on the left and right side of the plane. Once you jump, it’s about five seconds to the ground because you’ve got all that equipment on. It’s like dropping a watermelon from a rooftop downtown.”

Night jumps were different. Scarier. But by then, Chandler was committed to the path he’d chosen.

First taste of combat

His first overseas assignment was relatively calm — a peacekeeping mission where he didn’t have to fire his weapon. But that changed with his second deployment, four years later.

“Macedonia. That’s where things got real. Hearing all the gunfire, mortars, all that. I had to fire my weapon. I had to engage.”

He was 21 years old.

“It’s kill — or be killed — in that moment. You’re scared for your life, trying to save your life and your buddy’s life, thinking about your family you’ve got to get back home to. My oldest daughter was already born; my second daughter was on the way. I was like, ‘I got to get back. I got to get back to my mom and dad.'”

That deployment lasted about a year — a year of survival mode, of hypervigilance, of losing friends.

“Yeah, I lost some guys over there. Watching people close to you die right in front of your eyes — that’s different from seeing someone you don’t know pass away on the news. This is watching someone you know, someone in your formation, and they’re gone.”

When the body says stop

Chandler’s military career ended not with a clean retirement ceremony, but with a medical discharge. After returning from his combat deployment, he got orders to go back overseas.

“I’m like, ‘Man, I just came back from over there.’ But I had gotten injured — messed up my back on a bad landing during a jump. That medical retirement was probably a blessing in disguise.”

Ten years of service, multiple deployments, and now he was back in civilian life with injuries both visible and invisible.

The long road to understanding PTSD

For years after leaving the military, Chandler knew something was different about him, but he didn’t have a name for it.

“Back then, nobody told you what PTSD was. There was a stigma — you don’t want to be looked at as crazy. I didn’t want to be around people. I isolated myself. And as Black folks, we’ve been branded with that stigma that if you go talk to somebody, people think you’re crazy.”

He carried this alone for nearly a decade.

“It wasn’t until about 10 years ago that I sat down and talked to somebody about it. I was overanalyzing everything, hypervigilant all the time. I didn’t realize I was doing it — it was just embedded in me from those eight years of service. This is who I became.”

Sleep became a battlefield of its own.

“From time to time I’d have nightmares, wake up in sweat. For a long time, I wouldn’t go to sleep until like 2 or 3 in the morning. I’d hear gunshots, see my friends, my brothers who didn’t make it home.”

The military didn’t allow time to grieve properly, either for fallen comrades or family members back home.

“You can’t even grieve fallen soldiers that died before your eyes. You have to keep going. When their bodies go back to their hometown, that’s it — you don’t get to go to the funeral. You don’t get that closure.”

Finding help, one step at a time

Getting into therapy wasn’t easy. Chandler experienced mental health challenges for years, in part due to stigma surrounding mental health in the Black community.

“I didn’t want to be there at first. But once you start opening up, answering questions, you have no choice but to deal with it.”

PTSD doesn’t disappear, he learned, but you can develop tools to manage it.

“I just learned how to adapt and deal with it better. You still have it, but you learn coping mechanisms.”

The discipline from his military training actually helped in an unexpected way — the same focus and determination that got him through combat deployments now served him in managing his mental health.

But life had more challenges in store. In 2018, his father’s death triggered everything again.

“When my dad passed, that sent me into depression. I was spending every single day in the hospital for two weeks with him, watching him on those machines. Having to make decisions about whether to keep him on life support or let him go — it brought back all those feelings from losing people in the military.”

Part Two of Tyrone’s story explores how he discovered acting, landed a role on Tyler Perry’s “Meet the Browns,” and built his own production company while managing PTSD.

Resources

Immediate Help

Veterans Crisis Line – 24/7 help for veterans in crisis. Call or text 988 and press 1, or chat at 988lifeline.org.

Mental Health & PTSD Support

VA PTSD Program Locator – Search for local treatment programs, support groups, and counseling specifically for PTSD. Visit ptsd.va.gov.

Vet Centers – Community-based counseling centers for veterans and families, offering readjustment counseling, family support, and referrals. Call 877-927-8387 or search at va.gov/find-locations