Charles Pollard was supposed to be figuring out his senior year of high school when he found himself in the Saudi Arabian desert, M16 in hand, facing Iraqi forces at just 17 years old.

“My best friend joined the reserves and got all this praise from family and friends,” Charles remembers. “I was like, ‘Well, shoot, I want some of that love too.’ I joined thinking I’d just do boot camp, come back, and go to school and have it paid for. I never thought I’d see combat — that’s for sure.”

But Saddam Hussein had other plans. While Charles was in boot camp, Iraq invaded Kuwait, and what was supposed to be a simple reserve commitment became a deployment to Desert Storm.

A teenager in war

Charles was still 17 when he was called up for active duty in October 1990. By January 1991, he was moving forward with ground forces in the desert, part of the massive coalition pushing Iraqi forces out of Kuwait.

“We moved forward, moving forward, moving forward,” he says, the repetition still carrying the rhythm of that relentless advance decades later.

At 17, Charles found himself in situations no teenager should face.

“Did I kill anyone? Yeah. I didn’t see them, but with my artillery piece, we threw rounds down range. We were knocking down Iraqi positions.”

The weight of that reality — taking a life before he was old enough to vote — sits with him still.

One night stands out in Charles’s memory with terrifying clarity. “Hell Night”. His unit was moving into position in complete darkness when they realized they’d walked directly into an Iraqi stronghold.

“It was so dark I couldn’t see my hand in front of my face. We were setting up our position when we found out we were right on top of a bunch of Iraqis.”

The Iraqis were in tunnels beneath them. Had they been discovered, it would have been a deadly firefight at point-blank range.

“When we started setting up in that area, over the loudspeaker we heard Iraqi voices. We were like, ‘What the heck is going on?’ Then it sounded like it was like a countdown, and all of a sudden there was shooting — a huge, huge firefight.”

Charles’s best friend — the same one who’d convinced him to join — was caught in that firefight about a quarter mile away.

“That firefight was going on behind us, and I knew that’s where my friend was. I didn’t hear from him for three days. I just didn’t know.”

For a 17-year-old who’d known his best friend since he was eight years old, those three days felt endless.

“Three days later, he came up to my position. Man, we hugged each other like crazy. I’d been doing this with this man since I was eight years old. He’s my brother.”

Both teenagers had survived, but they’d been forever changed by what they’d seen and done.

Building a life after war

Charles served eight years total — first Marine Corps, then Air Force National Guard. After getting out of the Marine Corps, he found himself missing the structure and purpose of military life.

“I kind of missed it, so I went back to my unit in the Marines. But I was like, ‘This ain’t gonna work.’ So, I went to the Air National Guard.”

The Air Force offered him a spot in the medical field, which required training at Shepard Air Force Base and then to San Antonio at Wilford Hall for three to six months. It was a decision that would shape the rest of his life.

After leaving the Marine Corps in 1997, Charles worked in pharmaceutical care for several years. But it was his medical training in the Air Guard that opened doors to bigger opportunities. He eventually went back to school to become a Nurse Practitioner, working first in family practice before his son suggested something that changed his career trajectory.

“My son was like, ‘Dad, you should start your own practice.’ I was like, ‘I can do that?’ So, I started looking into it.”

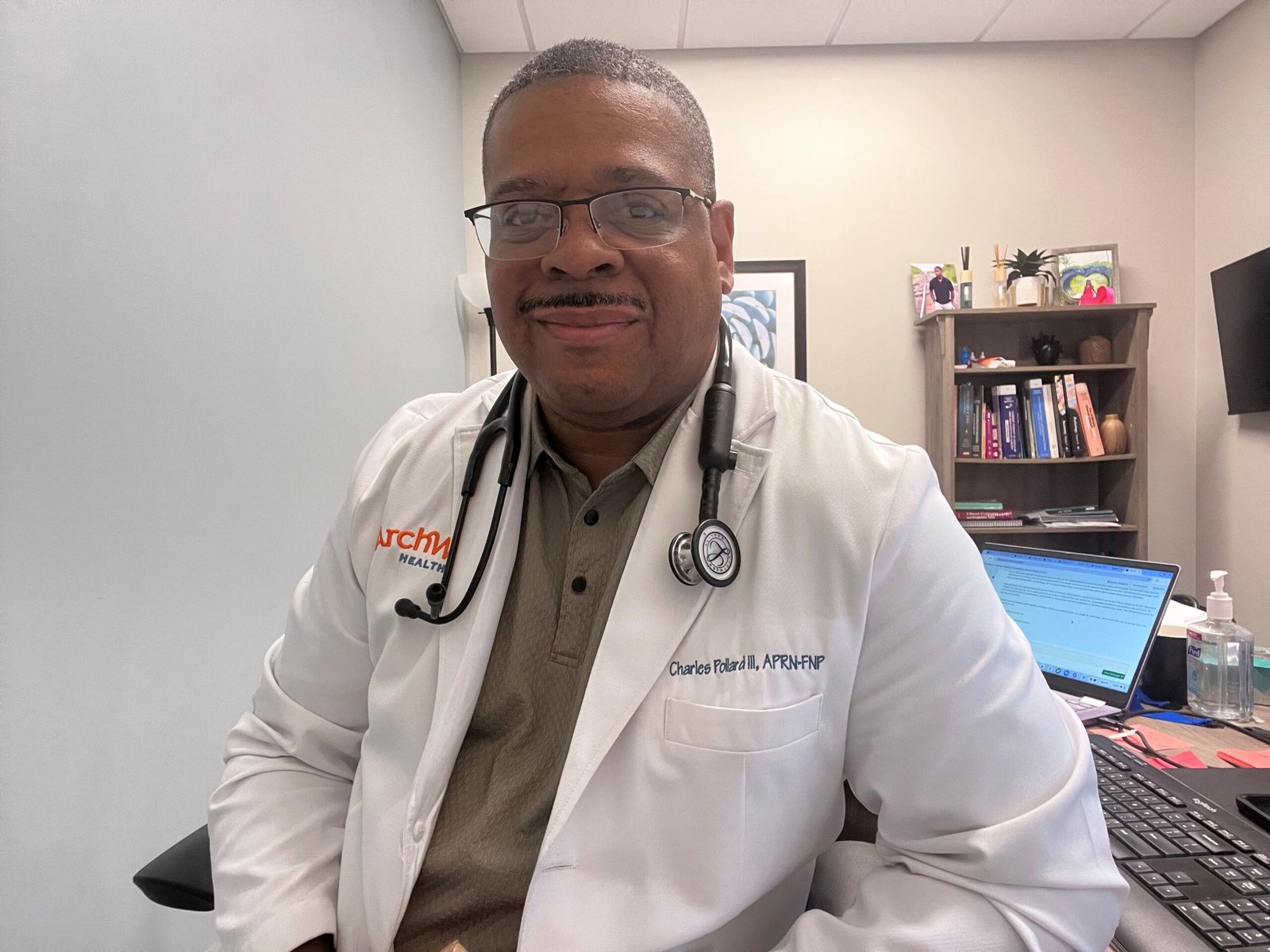

He opened his own medical practice, which he still operates today. But it’s his work with veterans that gives him the deepest sense of purpose.

“Right now, I do contract work — Veteran evaluation services. I work with veterans to help them get their benefits and ratings, through Compensation & Pension exams.”

Living with invisible wounds and helping others heal

Working with veterans every day, Charles has developed an eye for recognizing PTSD symptoms — partly because he lives with them himself.

“Do I have PTSD? Yeah, I do. A lot of my symptoms are anger. I get triggered easily, get angry at things that shouldn’t make me angry.”

His own struggle with PTSD helps him recognize it in the veterans who come through his office, even though his role is strictly physical evaluations.

“Most of them have PTSD. You can kind of tell — they get upset easily, overreact to things that shouldn’t bother them. You just know.”

But Charles has learned something important about managing his condition, something he can’t officially share with patients but demonstrates through his own professional demeanor.

“I know how to turn it off when I need to, for work. I’ve learned to compartmentalize.”

It’s a recognition that comes with its own weight. Charles sees the pain in other veterans’ eyes because he knows it from the inside. When a veteran sits across from him during an evaluation, there’s an unspoken understanding — one person who’s been there recognizing another who’s still struggling with the same invisible wounds.

Charles discusses his PTSD in a straightforward manner, similar to how many veterans approach ongoing conditions. The anger, the triggers, the hypervigilance — these are the ongoing costs of taking a life and seeing friends in mortal danger before he was old enough to understand what it would do to him long-term.

But Charles has found purpose in that experience. His own struggle with PTSD makes him a more effective advocate for other veterans, even within the limited scope of his medical practice.

“I work Monday through Friday, 8 to 5, and every Saturday morning I’m in the office seeing veterans. The VA sends me referrals, and I do the evaluations they need for their benefits.”

It’s not therapy or counseling — Charles handles the physical evaluations — but there’s healing in the work anyway. Every veteran he helps to get properly rated and compensated is another small victory against a system that doesn’t always serve those who served.

Understanding what others cannot

The casual “thank you for your service” that civilians offer feels hollow when you consider what Charles experienced before his 18th birthday.

“I understand people mean well when they say it. You can sympathize, but you can’t empathize unless you’ve been there. You don’t know what we’ve been through.”

Starting military service at 17 meant Charles never had the chance to be a normal teenager. He went straight from high school hallways to life-or-death situations in a foreign desert.

“At 17 years old, I thought I was going to die over there. The whole reason I joined was to get money for college. I was supposed to be in the reserves, but then we went to war.”

Charles’s story illustrates something important about military service: some of our veterans were children when they went to war. They made adult sacrifices before they had adult understanding of what those sacrifices would mean.

At 17, Charles was worried about getting money for college. Instead, he got trauma, purpose, medical training, and eventually a career helping other veterans navigate their own battles with invisible wounds.

“I just wish there was more I could do,” he says. “But I do what I can, one veteran at a time.”

Today, Charles’s work with veterans represents a kind of full-circle healing. The teenager who survived Desert Storm now uses his medical training to help other veterans navigate the complex process of getting disability benefits for their service-connected conditions.

It’s not the path Charles planned when he followed his best friend into the recruiter’s office. But it’s the path that’s allowed him to transform his own pain into purpose, his own survival into service to others who understand exactly what “thank you for your service” can never fully capture.

From teen soldier to healer, Charles has shown that survival can become service, and that even the deepest wounds can shape a life of purpose.

Resources

Immediate Help

Veterans Crisis Line – 24/7 help for veterans in crisis. Call or text 988 and press 1, or chat at 988lifeline.org.

Mental Health & PTSD Support

VA PTSD Program Locator – Search for local treatment programs, support groups, and counseling specifically for PTSD. Visit ptsd.va.gov.

Vet Centers – Community-based counseling centers for veterans and families, offering readjustment counseling, family support, and referrals. Call 877-927-8387 or search at va.gov/find-locations.

Disability Benefits

VA Disability Compensation – Information about disability ratings and benefits for service-connected conditions. Visit va.gov/disability or call 800-827-1000.

Veterans Service Organizations – Organizations like VFW, American Legion, and DAV provide free assistance with disability claims.

Flowers Law Firm – Legal support specializing in helping veterans navigate disability claims and appeals. Visit flowerslawfirm.info for more information.