From Air Traffic Controller to Truck Driver

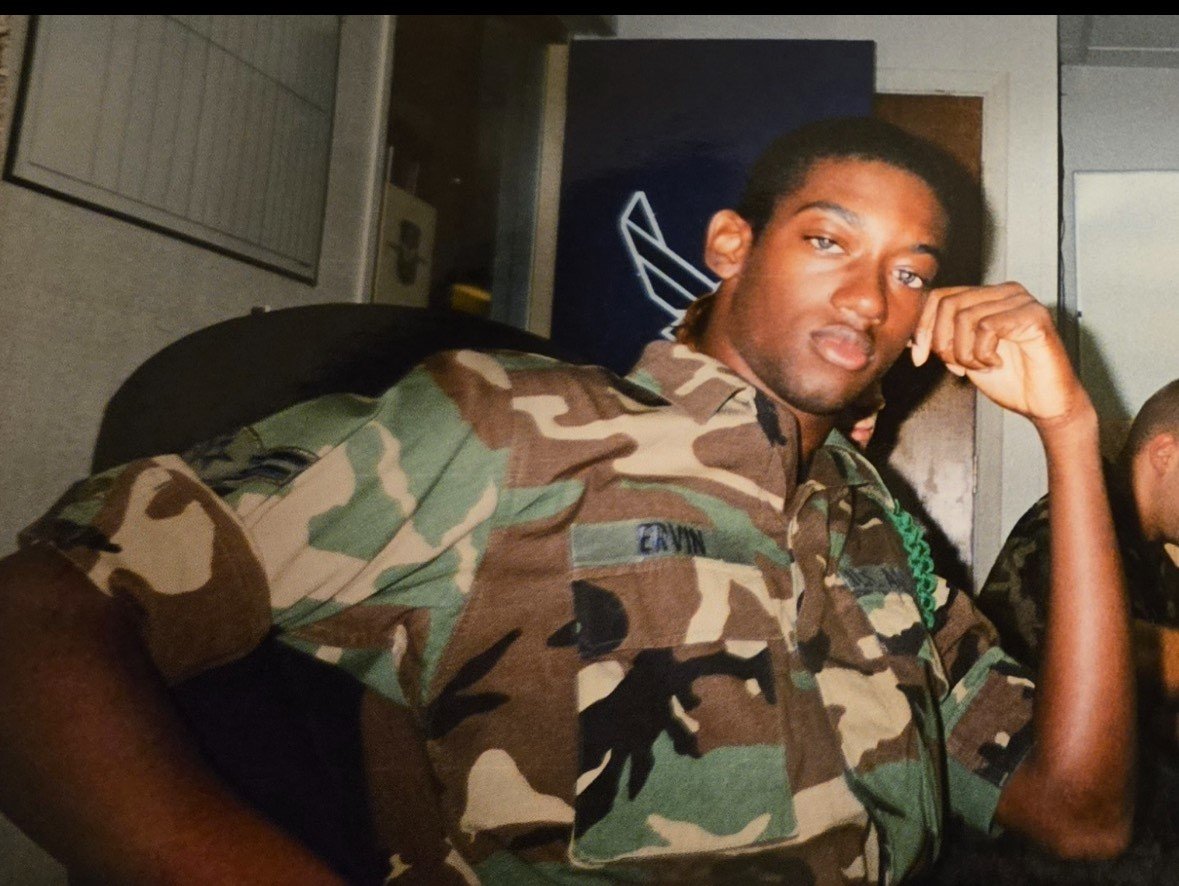

Pierce Ervin joined the Air Force in 2003 with dreams bigger than his circumstances. A standout athlete who had dominated track and field, he’d earned scholarship offers to both Johnson & Wales University and USC. But life had other plans. A relationship led to an unexpected pregnancy, and suddenly the 19-year-old found himself choosing military service over college athletics.

“I was actually going to go for track because I was pretty much dominating track,” Ervin recalls. “But then I ended up talking to somebody and got her pregnant. So I had to determine what I wanted to do.” The Air Force seemed like the perfect solution — he could support his child, continue running for the Air Force track team, and build a career. “Everything was just going to come into play that way.”

But military life didn’t unfold as planned. What followed was a four-year journey through air traffic control training, personal betrayal, and the kind of institutional isolation that leaves young service members adrift. Ervin’s story illuminates a harsh reality: for some veterans, the hardest battles begin when they come home.

Learning to Control the Sky

Air traffic control chose Ervin as much as he chose it. Known as one of the military’s most demanding and selective career fields, it requires split-second decision-making under extreme pressure. “I had to make 10 to 15 decisions every two to three seconds,” Ervin explains. “And you just have to keep doing it constantly.”

The job’s intensity is legendary — controllers can’t work more than certain hours without mandatory rest periods, and the stress can be overwhelming. “There’s actually a movie about it,” Ervin says, referencing “Pushing Tin” with Billy Bob Thornton and Angelina Jolie. “Basically, you can go crazy and end up killing people or killing yourself.”

Despite the pressure, Ervin found his calling in the tower. “I love air traffic control. I still dream about it, and this is almost 20 years later. It’s like something you can’t forget.” The work taught him invaluable skills about working with people and managing others. “As soon as you get out of training, they give you a trainee immediately. So, you have no choice but to work with this person — you have to understand their dialect, what they like to eat, just everything to try to help them become a better controller. Their failure is on you if they don’t get it.”

The experience developed patience he never knew he had. “It’s crazy because you wouldn’t think that I would have patience, but I have a lot more patience than I did. I didn’t have any when I was in high school.”

Betrayal and Isolation

But Ervin’s military experience was marked by profound personal and institutional failures. Despite having sponsors assigned to help him transition, he received virtually no meaningful guidance. “When I got to my duty station, yes, I was supposed to have a sponsor. I got there and they just did not do anything productive to help me.”

The financial transition was jarring. Going from making $6-7 an hour at jobs like McDonald’s and Bojangles to bringing home $900 every two weeks felt overwhelming for a 19-year-old. “It was $1,800 a month. Back then, that was a lot of money,” he remembers. But nobody helped him navigate this new financial reality or plan for his future.

The most devastating blow came on Valentine’s Day 2004. Ervin had been sending $1,000 of his $1,800 monthly income to support his girlfriend and what he believed was his child. During a visit home, her sister pulled him aside with crushing news: “Hey, you’ve been really treating my sister really nice. I appreciate you for being a good guy to her and everything. And I just want to let you know that the baby might not be yours.”

The paternity test confirmed his worst fears — 0% chance the child was his. “After that, I had no guidance. I was very cold. I didn’t care about how much money I was spending. I didn’t care about much of anything,” Ervin recalls. Despite his supervisors knowing about the situation, no one offered counseling or support. “Did they send me to the chaplain? Did they tell me to go talk to somebody? Never. Nobody said anything.”

The isolation was compounded by systemic failures. Ervin had completed four years of ROTC in high school, which should have accelerated his military rank. But his sponsors never told him he could take a test to advance to E4 within two years. “They didn’t tell me for weeks after I got to Georgia. I could have taken the test to go up a whole rank. They didn’t tell me whatsoever.”

The Six-Month Window

When Ervin left the Air Force in 2007, he discovered a cruel catch-22 that haunts many veterans in specialized fields: “After you get out of air traffic control, you have six months to find another job where you’re still proficient, and if you don’t, no one will hire you.”

The civilian air traffic control sector utilizes specific proficiency levels: level 5 refers to entry-level positions, level 7 typically represents individuals with around 20 years of experience and management responsibilities, while level 9 indicates decades of experience in the field. “They don’t want to train anybody. They want somebody proficient,” Ervin explains. “So, it was very hard to find a job.”

After four months of searching, Ervin finally found a position in Delaware. He’d arranged to stay with someone until he could afford his own place. Then disaster struck: “The person I was supposed to stay with until I got my first few paychecks — they got robbed. Someone kicked their door in and robbed them at gunpoint, and they moved back with their parents. So, I couldn’t accept the job.”

The missed opportunity was devastating. “It was very deflating. I didn’t care anymore. I just needed to get a job at that point.”

The Walmart Years

Unable to use his Air Force training, Ervin took a job at Walmart. The transition shattered his assumptions about work and advancement. His father had always told him to “stay on a job, work hard, and work your way up, and you’ll succeed.” But the economy had changed.

“Even though I was working hard, I was still not getting advancements, not getting the things that I should have gotten,” Ervin recalls. He was trained by the second-best person in the building, someone with 19 years of experience who taught him everything she knew. Customers specifically came to the store for his help. When a management position opened, he was confident he’d get it.

Instead, they gave it to someone with six months’ experience who lived an hour away. “I felt like I was doing everything is why I didn’t get it,” Ervin realizes now. He’d learned the hard lesson that making yourself indispensable can work against advancement — but he couldn’t stop working hard. “It was just stuck in me to do my best at my job. That’s what I’m supposed to do.”

The Pattern Repeats

This experience would repeat itself across multiple jobs — call centers, Wendy’s, and contracting positions. At one call center handling American Airlines medical benefits, Ervin spent an hour-and-a-half learning a new system and created a professional-looking reference document for the entire staff. Management loved it, American Airlines praised it, and they fired him two weeks later.

“Stuff like that, it’s like, why am I even trying? But then when I get on the next job, I continue to do it again,” Ervin says. “I don’t know, it’s very hard for me to not work hard because I’m used to working, because my father worked.”

His work ethic was forged in jobs like McDonald’s, where he helped run an entire restaurant on Friday nights with just four people — one on front counter, one on drive-through, one in the kitchen, one on grill. “We never got backed up. We ran to that store with four people. That’s the work ethic I was raised with.”

The College Gamble

Frustrated by being passed over for management positions, Ervin decided to pursue a business management degree. “Nobody would hire me for management positions, so I was like, well, maybe if I get a management degree, they’ll hire me.”

It made sense in theory, but the reality was different. He took on student loans despite the GI Bill covering tuition because he needed money to maintain his military standard of living. “I’m not supposed to be this broke. I’m a veteran. I’m supposed to have money. I’m supposed to have a good job.”

After graduation, every management position he applied for was downgraded to shift supervisor. Despite his military management experience training people for 2.5 years in complex technical roles, civilian employers wanted industry-specific experience.

“I never understand why jobs want you to have a background in the job before they hire you, which doesn’t make sense for a military veteran,” Ervin says. “In the military, you hire me for a job, all you have to do is teach me the job and I’ll do it better than anybody here. But they’re not going to do that. They want you to be proficient.”

Family Sacrifice and Rock Bottom

Ervin’s struggles intensified when he finally got a job at the airport — his dream of returning to aviation. But when his sister needed support during her pregnancy, he switched to third shift to help her. The sleep deprivation caught up with him, and he fell asleep at work. Getting fired from that airport job devastated him.

“I felt like a complete failure because I finally got a job at the airport. That’s all I needed to get back at the airport,” he recalls. “After that, I didn’t even know what to do anymore. Matter of fact, after that, I didn’t even apply for a job at all.”

The VA unemployment office eventually called him out of nowhere with a Wells Fargo position doing fraud detection. But even there, his commitment to customer service — taking time to ensure customers understood their situations — was seen as negative because it lengthened call times.

Finding Stability in Trucking

Today, Ervin drives trucks — a career he never wanted but that has given him financial stability. “I did not want to go into trucking at all whatsoever,” he admits. “Because I didn’t want to get stuck doing it, and there’s a lot of people that say when you start driving trucks, you’re stuck doing it.”

The job involves varying wake-up times, from as early as 4 AM to midnight, depending on the schedule. It offers a consistent income comparable to his previous earnings in the military. “It gave me back the life I once had in 2007,” he says, though he acknowledges he still wants more.

Lessons from the Road

Looking back, Ervin sees how crucial mentorship and guidance were — and how their absence shaped his struggles. His father, who was 41 when Ervin was born, worked 20-hour days but suffered brain damage from a workplace assault years earlier. “He knew what he knew, but math and science and resumes and computers, he didn’t know. I couldn’t ask him nothing.”

The lack of institutional support compounded these challenges. Simple things like not being told to turn in his military ID or learning about advancement opportunities months too late created unnecessary obstacles. “If I had someone when I was younger to help me make better decisions when I was in the military, I think I’d be a lot better off right now.”

Advice for Tomorrow’s Veterans

Ervin’s guidance for transitioning service members is hard-earned and practical: “When you get out, pick something and do it. Don’t wait around. I understand you might not enjoy it but do something. Don’t just do nothing and waste time. Life is short.”

He strongly advocates for veterans to stay in the military for a full 20-year career if possible. “If you go into the military, stay in the military. Do 20 and get retired. Getting out is not as easy as people make it seem. It’s not easy to get back here after you’ve been in, because once again, nobody cares that you’re in the military.”

For those pursuing education, his advice is research-based: “Look at the salary ranges. If the job pays between $30,000 and $80,000, you’re going to start at $30,000.” He learned this the hard way when his business management degree led to the same positions he could have achieved without college. “If you see a range, don’t get that job unless you love the bottom amount.”

Redefining Success

Ervin’s definition of success has evolved dramatically since his military days. “When I was in the military, success was like, I needed a million dollars. That’s when you know you’re somebody,” he reflects. “Now it’s just having your kids have everything they need and being happy on a daily basis.”

He considers himself successful today, though different from his military years. “I have everything that I need and want. I just want more.” The difference is perspective — as a single man in the military, he had fewer responsibilities and more freedom. Now, with children to support, his priorities have shifted.

What Employers Need to Know

For civilian employers, Ervin emphasizes looking beyond imperfect resumes to see character and work ethic. “It’s probably a good thing to have a heart-to-heart with a person. Talk to the person, see what they have going on in life. Determine their character.”

Not every veteran has the same background or values, he notes, but many bring a work ethic that’s increasingly rare. “Everybody doesn’t know how to go to work and work hard to work your way up to the top. Everybody doesn’t know that when you come to work, you come to work to work. It’s not about a paycheck. The money is going to come. Sometimes it’s about the people. Sometimes it’s about the mission.”

Pierce Ervin’s journey from confused recruit to skilled air traffic controller to struggling veteran to stable truck driver illustrates both the failures and possibilities of military transition. His story is a reminder that behind every veteran’s resume is a human being who has served their country and deserves more than bureaucratic indifference.

“I wish I had somebody when I got out — before I got in — that could have helped me a whole lot more than what I had,” Ervin reflects. “Because they did nothing.”

For Ervin, success isn’t about reaching that million-dollar goal he once set. It’s about stability, family, and the hard-earned wisdom that sometimes the most important battles are the ones fought after you come home.

Resources for Veterans

Veterans Crisis Line

Dial 988, then press 1 | Text: 838255 | Chat: veteranscrisisline.net

Confidential, 24/7 support for veterans in crisis or emotional distress.

Military OneSource

Phone: 800-342-9647 | militaryonesource.mil

Free career coaching, resume writing, interview preparation, and job search assistance for veterans and military families.

Corporate Gray

corporategray.com

Career transition programs specifically designed for military professionals, including skills translation and networking.

VET TEC Program

va.gov/education/about-gi-bill-benefits/how-to-use-benefits/vr-e/

VA funding for technology training and certifications to help veterans transition into high-demand tech careers.

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Veterans Programs

faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ahr/careers_jobs/veterans/

Specific programs to help military air traffic controllers transition to civilian ATC positions.

SkillBridge Program

skillbridge.osd.mil

Industry training and apprenticeships during the last 180 days of military service.

Hire Heroes USA

hireheroesusa.org

Free career coaching, resume translation, and job placement assistance specifically for veterans and military spouses.

Student Veterans of America

studentveterans.org

Support for veterans navigating education benefits and career transitions through college.

ReServe

reserveinc.org

Matches experienced professionals (including veterans) with nonprofits and social impact organizations for meaningful work.

American Corporate Partners (ACP)

acp-usa.org

Free mentorship program pairing veterans with corporate professionals for career guidance and networking.